What Makes Dickens’ Characters Immortal?

How often one really thinks about any writer, even a writer one cares for, is a difficult thing to decide; but I should doubt whether anyone who has actually read Dickens can go a week without remembering him in one context or another. Whether you approve of him or not, he is there, like the Nelson Column. At any moment some scene or character, which may come from some book you cannot even remember the name of, is liable to drop into your mind. Micawber's letters! Winkle in the witness-box! Mrs. Gamp! Mrs. Wititterly and Sir Tumley Snuffim! Todgers's! (George Gissing said that when he passed the Monument it was never of the Fire of London that he thought, always of Todgers's.) ... Squeers! Silas Wegg and the Decline and Fall-off of the Russian Empire! Miss Mills and the Desert of Sahara! Wopsle acting Hamlet! Mrs. Jellyby! Mantalini, Jerry Cruncher, Barkis, Pumblechook, Tracy Tupman, Skimpole, Joe Gargery, Pecksniff -- and so it goes on and on. It is not so much a series of books, it is more like a world." George Orwell

What quality is it that these Dickens characters have which makes them so memorable? Why are they still alive to readers all over the world, all his novels still in print in multiple editions, when so many excellent novelists of his Victorian era and much later are today read by comparatively few people outside the universities? Many have suggested that it has something to do with his moving so boldly beyond the realism of his own age, as each era has its own ideas of what constitutes realism, but those ideas go out of fashion. Was the secret Dickens's ability to use dramatic exaggeration and poetic metaphor to turn his fictional people from mere realistic characters into mythological beings who transcend passing tastes, transcend time?

Virginia Woolf – A Dickens Fan?!

(Virginia Woolf was representative of the Modernist generation of writers who, shaped by the disillusionment of World War One and rapid technical/industrial changes, felt themselves to be in a very different world and literary universe from that of Dickens. So, not surprisingly, they recoiled from his fiction as suspect ideologically and aesthetically — finding it too traditional in values, too popular with the mass of readers and too exaggerated in technique. But here in her mid-fifties — freed from her former “crabbings and diminishings”— Woolf re-reads a favorite novel of his and is shocked at how good it is. – Menalcus)

Michael Slater says: “Claire Tomalin sent me this a while ago. Virginia Woolf is writing to Hugh Walpole 8 February 1936: ‘I’m reading David Copperfield for the 6 time with almost complete satisfaction. I’d forgotten how magnificent it is. What’s wrong, I can’t help asking myself? Why wasn’t he the greatest writer in the world? For alas – no, I won’t try to go into my crabbings and diminishings. So enthusiastic am I that I’ve got a new life of him. …’ Claire came across it in Congenial Spirits: Selected Letters of Virginia Woolf, edited by J.T.Banks (1989).”

From the London Particular, July 2014

Psychiatrists and Counselors in Baltimore Study a Christmas Carol for Its Insights

(from a 2001 article in the Baltimore Sun)

Dickens: Ghost of a Freudian Future?

Seeing Scrooge, Ghosts as Pioneers of Psychotherapy

Ideas: Therapy Lit

December 23, 2001|By Arthur Hirsch | Sun Staff

Charles Dickens was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. Dickens was gone and buried in Westminster Abbey long before Sigmund Freud emerged as the Father of Psychoanalysis.

This must be distinctly understood, or nothing wonderful could come of the theory being advanced by Baltimore psychiatrist Stephen E. Warres, much to the interest and amusement of his colleagues at Sheppard Pratt. Dickens was dead as a doornail by the turn of the century, when Freud conducted his early expeditions into childhood experience and talk therapy. Nonetheless, Warres argues, Dickens anticipated this therapeutic revolution by more than a half-century when he wrote A Christmas Carol.

It's unlikely Ebenezer Scrooge would have coughed up the shillings for a co-pay, much less the full price of psychotherapy, so it hardly mattered to him that, in his day, there were no such practitioners. It happens that Scrooge didn't need them, not with all those ghosts. It was just a matter of when the miserable old tightwad would want to change.

"He's having an assisted introspection and review of his life," says Warres, who works at the Forbush School of the Sheppard Pratt Health System. "That's what psychotherapy is."

Imagine the surprise of more than 100 psychiatrists and social workers when they took their seats in the conference center at Sheppard Pratt recently for the twice-monthly lecture called "Grand Rounds." In keeping with the customary presentations on a patient or treatment regimen, the schedule announced "The Case of Ebenezer S." With PowerPoint illustrations, no less.

"I found the argument was compelling," says Scott Aaronson, a psychiatrist and the director of clinical research programs. It shed light on some fundamental questions: "By what means do people change? What will lead people in the direction of change?"

Warres, whose specialty is child and adolescent psychiatry, went the full 90 minutes. He held that A Christmas Carol is "nothing less than a primer of psychotherapy, so far ahead of its time that it could not be recognized as such, even by its author, until the world had caught up with its ideas."

Journey to self-awareness

A great popular success when published in 1843 and thereafter, the book is usually dismissed by scholars as a trifle in a grand literary career. Warres doesn't argue that it's a great book; rather, he applauds its psychological insights and the way Dickens makes Scrooge's transformation believable by showing a process that serves as a "model of psychotherapy."

The ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future act as psychotherapists, says Warres, conducting Scrooge on a journey toward self-awareness and a more full and happy life.

That would seem to make the ghost of Scrooge's partner, Jacob Marley, the primary care physician, as he effectively "refers" the aging skinflint to the treatment offered by not one, but three specialists. No wonder Scrooge at first seems exhausted by the prospect.

"Couldn't I take 'em all at once, and have it over, Jacob?" Scrooge asks. No chance.

Scrooge, Warres told his audience, "has fallen under a kind of outpatient commitment," his resistance to the treatment program crumbling as the story unfolds.

There is first the matter of belief. Scrooge protests that he doesn't believe Marley's Ghost is a ghost at all. Something he ate, perhaps, playing havoc with his senses. A bit of Marley wailing and chain-rattling settles the matter, however, as a terrified Scrooge falls to his knees and acknowledges that he believes.

A good thing. As Warres told his audience: without belief in the therapist, the likelihood of progress is severely diminished, if not precluded. Jerome Frank -- Johns Hopkins psychiatrist and psychotherapy pioneer -- wrote about this in Persuasion and Healing, but not before Dickens wrote about it in A Christmas Carol.

The book anticipated a legion of theorists, Frank and Freud, among others, says Warres.

If Clarence Schultz, in the University of Maryland's Primer of Psychotherapy, argues that qualities associated with women, such as patience, caring, and receptivity, are essential to the effective therapist, Dickens knew that too. The grasp of the Ghost of Christmas Past, "though gentle as a woman's hand, was not to be resisted."

As a psychiatrist and therapeutic hypnotist, Milton H. Erickson would guide patients back to their pasts, often with stops at significant occasions such as birthdays or holidays. Dickens also understood the power of this strategy. By seeing scenes of himself as a schoolboy abandoned by his father and other boys, and by seeing how he spurned a young love to pursue his career, Scrooge reacquaints himself with his wounded self.

As Sheppard Pratt psychiatrist Harry Stack Sullivan understood mental health as the ability to see yourself as others do, so did Dickens. In the course of the story, Scrooge glimpses himself through the eyes of family and business associates, courtesy of the spirits of Christmas Present and Future.

What a motley crew these ghosts make. The first is a kind of hermaphrodite of uncertain age and unstable form; the second a jovial giant, the third a hooded specter pointing a bony finger but uttering not a word. They could easily represent "three aspects of a single therapist," says Warres, or at least a range of therapeutic approaches: variously insistent and passive, chatty and silent, gentle and stern. Economical, too

Like the typical patient, Scrooge shows a spectrum of responses. He resists, acquiesces, and actively participates. He finds the process a torture, he finds it liberating. He's angry and grateful with the ghosts. The man who began the process considering Marley a "humbug" ends up celebrating on Christmas morning: "The Spirits have done it all in one night. They can do anything they like. Of course, they can."

Such life-changing work accomplished in such a short time would surely cheer the heart of any managed-care bean counter. Warres told his audience that he had submitted the Case of Ebenezer S. for review to "Dr. Les Kost" of Seamless Behavioral Health. Kost wrote back, he said, delighted to find that the case provided "scientific evidence to justify our new policy of restricting all psychotherapy to three sessions at a maximum."

Note the turned tables. Compelled by economics and too much faith in the quick pharmaceutical fix, the contemporary practitioner plays the role of an unreformed Scrooge. Charles Dickens may not have invented psychotherapy, Warres says, but he appears to have seen it coming.

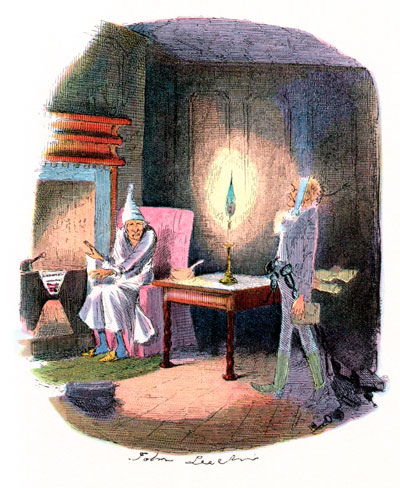

Is Marley's ghost (come to warn Scrooge above) similar to a "Primary Care Physician", referring him to three ghost "therapists"?

Great Expectations from great literature … empathy occurs in the spaces between characters, such as Joe and Pip, pictured here in the 2012 film adaptation. Photograph: Moviestore/Rex Features. Story below.

Reading literary fiction improves empathy, study finds. ~~ the Guardian, Oct 8, 2013

New research shows works by writers such as Charles Dickens and Téa Obreht sharpen our ability to understand others' emotions – more than thrillers or romance novels.

Have you ever felt that reading a good book makes you better able to connect with your fellow human beings? If so, the results of a new scientific study back you up, but only if your reading material is literary fiction – pulp fiction or non-fiction will not do.

Psychologists David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano, at the New School for Social Research in New York, have proved that reading literary fiction enhances the ability to detect and understand other people's emotions, a crucial skill in navigating complex social relationships.

In a series of five experiments, 1,000 participants were randomly assigned texts to read, either extracts of popular fiction such as bestseller Danielle Steel's The Sins of the Mother and Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, or more literary texts, such as Orange-winner The Tiger's Wife by Téa Obreht, Don DeLillo's "The Runner", from his collection The Angel Esmeralda, or work by Anton Chekhov.

But the pair then used a variety of Theory of Mind techniques to measure how accurately the participants could identify emotions in others. Scores were consistently higher for those who had read literary fiction than for those with popular fiction or non-fiction texts.

"What great writers do is to turn you into the writer. In literary fiction, the incompleteness of the characters turns your mind to trying to understand the minds of others," said Kidd.

Kidd and Castano, who have published their paper in Science, make a similar distinction between "writerly" writing and "readerly" writing to that made by Roland Barthes in his book on literary theory, The Pleasure of the Text. Mindful of the difficulties of determining what is literary fiction and what is not, certain of the literary extracts were chosen from the PEN/O Henry prize 2012 winners' anthology and the US National book awards finalists.

"Some writing is what you call 'writerly', you fill in the gaps and participate, and some is 'readerly', and you're entertained. We tend to see 'readerly' more in genre fiction like adventure, romance and thrillers, where the author dictates your experience as a reader. Literary [writerly] fiction lets you go into a new environment and you have to find your own way," Kidd said.

Transferring the experience of reading fiction into real-world situations was a natural leap, Kidd argued, because "the same psychological processes are used to navigate fiction and real relationships. Fiction is not just a simulator of a social experience, it is a social experience."

Not all psychologists agreed with Kidd and Castano's use of Theory of Mind techniques. Philip Davies, a professor of psychological sciences at Liverpool University, whose work with the Reader Organisation connects prisoners with literature, said they were "a bit odd".

"Testing people's ability to read faces is a bit odd. The thing about novels is that they give you a view of an inner world that's not on show. Often what you learn from novels is to be a bit baffled … a novel tells you not to judge," Davies said.

"In Great Expectations, Pip is embarrassed by Joe, because he's crude and Pip is on the way up. Reading it, you ask yourself, what is it like to be Pip and what's it like to be Joe? Would I behave better than Pip in his situation? It's the spaces which emerge between the two characters where empathy occurs."

The five experiments used a combination of four different Theory of Mind tests: reading the mind in the eyes (RMET), the diagnostic analysis of non-verbal accuracy test (DANV), the positive affect negative affect scale (PANAS) and the Yoni test.

However, although Castano and Kidd proved that literary fiction improves social empathy, at least by some measures, they were not prepared to nail their colours to the mast when it came to using the results to determine whether a piece of writing is worthy of being called literary.

"These are aesthetic and stylistic concerns which as psychologists we can't and don't want to make judgments about," said Kidd. "Neither do we argue that people should only read literary fiction; it's just that only literary fiction seems to improve Theory of Mind in the short-term. There are likely benefits of reading popular fiction – certainly entertainment. We just did not measure them."

What a comfort and teacher great literary fiction can be! Consider this brief personal account from a former leader of the British government.

Dickens The Comforter

Gillian Reynolds, radio critic for the Daily Telegraph, recently praised a programme in the “The Book That Changed Me” series, which featured former Labour Home Secretary, Alan Johnson, talking about David Copperfield. Johnson lived with his mother and elder sister in a Paddington slum, his father having run off years earlier. When he was 13 his mother died suddenly in hospital. He’d been sent to stay with the Coxes, family friends. The day his mother died, Mr Cox unlocked the book cabinet and allowed him to choose a book. He chose DC and the novel became his constant companion for a year. Tears fell for nurse Peggotty, he said, that didn’t for his mother. When rehoused with his sister in a council flat in Battersea, far from home, DC saw him through.

~~ from London Particular, a publication of the Dickens Fellowship, March 2014.

Tony Pointon, emeritus professor at the University of Portsmouth in England, gives a delightfully economical refutation of this "all alike" myth:

“Because somebody formulated a theory that Dickens did not understand women, and someone else said all his women were of one type – a "fact" often repeated to me by students of English Literature - … one finds these ideas have become "general knowledge" like so many things in biography. Taking just one novel (Our Mutual Friend), how can anyone say that there is a single template for Mrs Wilfer, Bella Wilfer, Lavinia Wilfer, Lizzie Hexam, Jenny Wren, Pleasant Riderhood, Abbey Potterson, Mrs Lammle, Lady Tippins, Mrs. Veneering, Betty Higden, Mrs Boffin, Miss Peecher, etc.?” -- from a post to the UCSB Dickens Forum.

Touche! For anyone who has read this novel, pause for a second to remember each of those thirteen female characters and consider how strikingly different, and real, they still are in memory. What a colorful ménage!

Menalcus's interpretive essay on Bleak House is here:

The Dickensian

Edited by MALCOLM ANDREWS

Associate Editor: TONY WILLIAMS Picture Research: FIONA JENKINS

Fellowship Diary and Branch Lines: ELIZABETH VELLUET

Published three times a year by the Dickens Fellowship, The Charles Dickens Museum, 48 Doughty Street, London WC1N 2LF.

(See opposite for details concerning Subscriptions and Contributions.)

Summer 2011 No. 484 Vol. 107 Part 2 ISSN 0012-2440

CONTENTS

Editorial 99

Notes on Contributors 100

Bleak House: A Tale of Two Retreats 101

MENALCUS LANKFORD

Dickens and the Southsea Pier Hotel: A Note 112

GEOFFREY CHRISTOPHER

The ‘Our Parish’ Curate 115

KEITH HOOPER

William Makepeace Thackeray: A Bicentennial Tribute 124

JEREMY TAMBLING

The Letters of Charles Dickens: Supplement XV 126

ANGUS EASSON LEON LITVACK

MARGARET BROWN JOAN DICKS

Book Reviews

JEREMY CLARKE on Juliet John’s Dickens and Mass Culture 145

FRANCO MARUCCI on two volumes of essays on Dickens, 147

Italy and the Victorians

TONY WILLIAMS on Dickens’s Dreadful Almanac 149

BERYL GRAY on Dickens connections to the history of the 151

Battersea Dogs Home

Brief Notices 153

Theatre Reviews

ALEX PADAMSEE on an adaptation of Great Expectations to 155

1860s India

JEREMY TAMBLING on Hard Times at Murrays’ Mills, 157

Ancoats

Conference Review

TONY WILLIAMS on ‘Dickens and Medicine’ at the Royal 161

Society of Medicine

Fellowship Notes and News 164

When Found Fellowship News, Diary and Branch Lines

Report of ‘Dickens Weekend’ at Christchurch, New Zealand