2014: New Statue Erected in Dickens's Birthplace City of Portsmouth

At the unveiling in 2014, a boy was encouraged to have his picture taken with an author who had written about children with such understanding.

(His name is Oliver, and he is pictured with the statue of his great-great... grandfather.)

Dickens was always to preserve that two-fold character of a man who has seen much, and has viewed things with the eyes of a child. ~~ Andre Maurois

From the website of

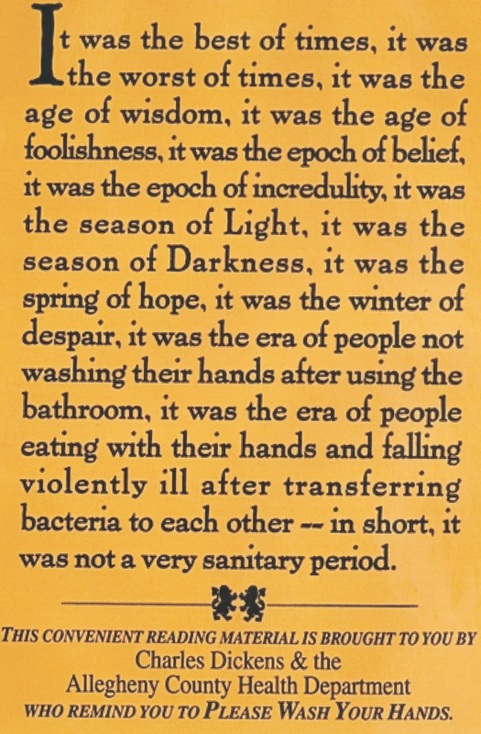

the Allegheny County Health Department (Pittsburgh, PA“A major outbreak of shigellosis — an intestinal illness often associated with poor handwashing practices — prompted ACHD and a local ad agency to develop a series of restroom posters that were based on the works of famous authors like Charles Dickens.” Once the posters were put up in restrooms, “Shigellosis cases dropped dramatically and surveys found handwashing rates to be much higher in restrooms where the posters were displayed.” Poster below

2008 Review by R. B. Bernstein, Distinguished Adjunct Professor of Law, New York Law School, on Norton's re-issue of its 1977 Critical Edition of Bleak House.

The first time that I encountered Charles Dickens’s BLEAK HOUSE was in the spring of 1978, in my first-year civil procedure course at Harvard Law School. The grand master of procedure, Professor Arthur R. Miller, was stalking the lecture hall, discussing an issue of complex litigation, holding us in rapt attention. In passing, he mentioned “a real Jarndyce and Jarndyce situation.” Suddenly the spell broke, and he was aware of it. He looked at his 150 confused students and repeated, with emphasis, “Jarndyce and Jarndyce,” hoping to jog our memories. Then he demanded, “How may of you have read BLEAK HOUSE?” Only a handful of students raised their hands; I was not among them. He raised his hands like Moses getting ready to part the Red Sea in “The Ten Commandments” and proclaimed, “All of you should read BLEAK HOUSE. Anyone engaged with law should read BLEAK HOUSE. It is the one indispensable book.” As an obedient law student, I marched to Harvard Square, bought a Penguin Classics edition of BLEAK HOUSE, and started to read. Three days later, I finished the book, dazed and awed. I understood why Professor Miller had been so insistent.

(Now) for fifteen years, I have taught that course, concluding each semester with a close reading of BLEAK HOUSE. This vast, somber book serves a vital purpose in the course as I’ve structured it. …

…